As I type this, I am sitting at a courtesy computer in the hallway of a cancer ward on the third floor of a children's hospital. I am just outside my son's room, inside of which he sleeps peacefully, aided by the somnolent drift of Atavan and morphine and Benadryl through his bloodstream. It has been a long three months that has brought us here, to this night in this place. The clock at the bottom right hand of the computer screen says it's one a.m., which means that today's the day; in approximately ten hours, a nurse will start the blood transfusion that will determine the course of the rest of our lives.

The story in its entirety is a long one, and I have been fighting to tell it for many weeks. In fact, I don't know that I've ever struggled with writing like the telling of this tale has brought, and the fight still isn't over. Then again, nothing this important has ever happened to me. It becomes incredibly difficult, I've found, to shape the words that will convey how your entire life has changed in a few short moments, and you can spend innumerable sleepless nights examining and reexamining the details that surround those few moments, turning them over and over in your hands, trying to make sense of it, to find a pattern, some semblance of math or reason that would seem to add up to what has happened, who you've become, how the world looks and feels to you now, from this new perspective, through these new eyes. But it can't be done, of course. It's like taking a single piece from a thousand different puzzles and then trying to fit them all together to make an image you've picked at random from volume Nam-thru-Op of the encyclopedia. Even if you could manage to force the pieces together, maybe snipping off an extraneous tab with scissors here or there, you still can't fashion a picture that makes any sense.

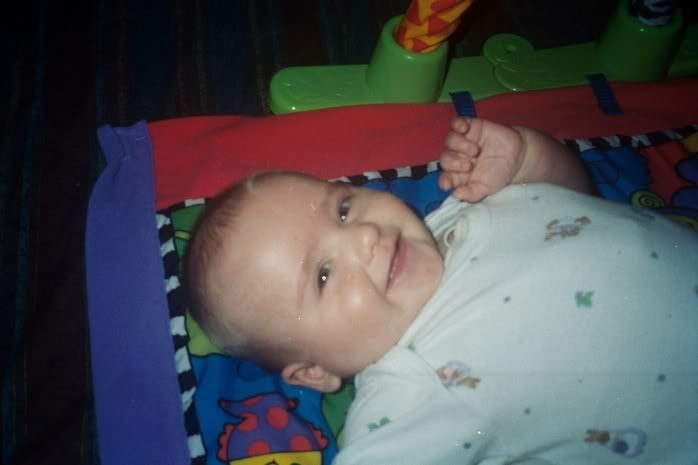

I've written many pages about the events of the last three months of my family's lives, none of which fit together particularly well, and none of which can explain what has happened. At some point I may manage to assemble these bits and pieces into a moderately coherent whole, perhaps even for the pages of this very journal, but until then, this thumbnail sketch will have to suffice. The short of it is that my wife and I took our son to the hospital the weekend of Memorial Day with a persistent high fever. Less than a week later, his abnormal test results led doctors to their diagnosis of a rare blood disorder called Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis. The disease isn't classified as cancer, but it essentially behaves the same way as cancer and so is approached using a similar course of treatment. Our little Jeremy has handled it all like the brilliant, ebullient, tireless star that he is, with smiles and laughter in the face of so much ugliness and suffering. Through six weeks of the initial chemotherapy, his mood and character were so bright and delighted that you could never have guessed how sick he was if it hadn't been for the thin rubber IV line that sprouted from a tiny hole in his chest to poke out between the snaps in his onesies, or the steadily receding hairline that eventually left him bald as a cueball for the first time since before he was born, or the way his diapers would smell the first few days after a treatment (most chemotherapy is processed by the kidneys and leaves the patient's urine smelling strongly chemical, not unlike something burning on the eye of a stove). His remarkably constant good humor has made this ordeal infinitely easier for his mother and I to shoulder.

Still, it has taken its toll, on all of us. The past two weeks have been the toughest thus far, comprising the most intensely concentrated barrage of chemicals to his system, and it's finally begun to show in more upsetting ways. His appetite has completely dried up, leaving him to receive all of his nutrition through the IV now, and when he vomits (which happens at least four times daily, regardless of round-the-clock nausea medication), it is only a slick translucent green bile, just like the awful stuff we find in his diapers. His skin is dotted with hives, and mucousitis lines his throat and the inside of his mouth with sores, making even thumb-sucking too painful to endure. There are headaches, chills, and fever. He cries often now, whereas he so rarely did before, and the cry is pronouncedly different from the moderate urging tone to which we'd grown accustomed, sounding so mournful as to require enormous patience and courage from Holly and I to keep from bursting into uncontrolled sobs at the sound of it. The smiles and laughter from our happy boy are much fewer and farther between these past few days, and it is to us as if the sun has suddenly disappeared from the sky. And yet, we know the worst is far from over. All this recent hammering down of his immune system has been leading up to today - at 11 a.m. he will receive a bone marrow transplant that will hopefully negate the disease entirely and leave the three of us to lead relatively normal lives from this point forward. Whatever normal is anymore. I'm fairly sure I never knew in the first place.

For those of you that hadn't already connected points A and B, it was our family to which Poppyseed's generous entries about her friends' sick baby referred. The handful of 'bard denizens who learned of our plight through their kind inquiries regarding my prolonged absence from these pages have been wonderfully supportive, as have all our other friends and family, and I cannot thank them enough. Your words of comfort and concern have made a huge difference to me, and I'll never forget them. Please continue to keep us in your thoughts and, if you are inclined to such, your prayers as well.

Jeremy was 25 weeks old yesterday; he has spent more than half of his life now with radioactive chemicals coursing through his veins. I keep telling Holly to try not to worry too much. I tell her that this is always how superheroes are born.

As footnote: I can't sleep tonight. The strain and stress of the coming transplant have rendered my mind's shutters useless, and they've been stuck wide open for the last three days or so. Last night I cleaned our house (which is an empty, lonely place since Holly and Jeremy took up residence here at the hospital again) within an inch of its life. Tonight I wandered the vacant hallways of the hospital, eventually making my way down to the ground floor, where there is a bay of vending machines filled with all manner of bad food. I walked over to the only Coke machine I've found in the entire hospital that dispenses cans rather than those plastic bottles (Holly thinks I'm completely mental, but I swear the soda tastes different from one container versus the other, and I much prefer the cans), deposited 65 cents, and pressed the button for regular Coca-Cola. There was a huge CRASH! from inside the machine, and I watched in amazement as the issuing chute at the bottom of the machine filled with cans. For my 65 cents, I was dispensed nine ice cold Cokes.

It may seem silly, but I believe that providence can announce itself in silly ways sometimes. It was just after midnight when I pushed that button. I feel lucky today.

The story in its entirety is a long one, and I have been fighting to tell it for many weeks. In fact, I don't know that I've ever struggled with writing like the telling of this tale has brought, and the fight still isn't over. Then again, nothing this important has ever happened to me. It becomes incredibly difficult, I've found, to shape the words that will convey how your entire life has changed in a few short moments, and you can spend innumerable sleepless nights examining and reexamining the details that surround those few moments, turning them over and over in your hands, trying to make sense of it, to find a pattern, some semblance of math or reason that would seem to add up to what has happened, who you've become, how the world looks and feels to you now, from this new perspective, through these new eyes. But it can't be done, of course. It's like taking a single piece from a thousand different puzzles and then trying to fit them all together to make an image you've picked at random from volume Nam-thru-Op of the encyclopedia. Even if you could manage to force the pieces together, maybe snipping off an extraneous tab with scissors here or there, you still can't fashion a picture that makes any sense.

I've written many pages about the events of the last three months of my family's lives, none of which fit together particularly well, and none of which can explain what has happened. At some point I may manage to assemble these bits and pieces into a moderately coherent whole, perhaps even for the pages of this very journal, but until then, this thumbnail sketch will have to suffice. The short of it is that my wife and I took our son to the hospital the weekend of Memorial Day with a persistent high fever. Less than a week later, his abnormal test results led doctors to their diagnosis of a rare blood disorder called Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis. The disease isn't classified as cancer, but it essentially behaves the same way as cancer and so is approached using a similar course of treatment. Our little Jeremy has handled it all like the brilliant, ebullient, tireless star that he is, with smiles and laughter in the face of so much ugliness and suffering. Through six weeks of the initial chemotherapy, his mood and character were so bright and delighted that you could never have guessed how sick he was if it hadn't been for the thin rubber IV line that sprouted from a tiny hole in his chest to poke out between the snaps in his onesies, or the steadily receding hairline that eventually left him bald as a cueball for the first time since before he was born, or the way his diapers would smell the first few days after a treatment (most chemotherapy is processed by the kidneys and leaves the patient's urine smelling strongly chemical, not unlike something burning on the eye of a stove). His remarkably constant good humor has made this ordeal infinitely easier for his mother and I to shoulder.

Still, it has taken its toll, on all of us. The past two weeks have been the toughest thus far, comprising the most intensely concentrated barrage of chemicals to his system, and it's finally begun to show in more upsetting ways. His appetite has completely dried up, leaving him to receive all of his nutrition through the IV now, and when he vomits (which happens at least four times daily, regardless of round-the-clock nausea medication), it is only a slick translucent green bile, just like the awful stuff we find in his diapers. His skin is dotted with hives, and mucousitis lines his throat and the inside of his mouth with sores, making even thumb-sucking too painful to endure. There are headaches, chills, and fever. He cries often now, whereas he so rarely did before, and the cry is pronouncedly different from the moderate urging tone to which we'd grown accustomed, sounding so mournful as to require enormous patience and courage from Holly and I to keep from bursting into uncontrolled sobs at the sound of it. The smiles and laughter from our happy boy are much fewer and farther between these past few days, and it is to us as if the sun has suddenly disappeared from the sky. And yet, we know the worst is far from over. All this recent hammering down of his immune system has been leading up to today - at 11 a.m. he will receive a bone marrow transplant that will hopefully negate the disease entirely and leave the three of us to lead relatively normal lives from this point forward. Whatever normal is anymore. I'm fairly sure I never knew in the first place.

For those of you that hadn't already connected points A and B, it was our family to which Poppyseed's generous entries about her friends' sick baby referred. The handful of 'bard denizens who learned of our plight through their kind inquiries regarding my prolonged absence from these pages have been wonderfully supportive, as have all our other friends and family, and I cannot thank them enough. Your words of comfort and concern have made a huge difference to me, and I'll never forget them. Please continue to keep us in your thoughts and, if you are inclined to such, your prayers as well.

Jeremy was 25 weeks old yesterday; he has spent more than half of his life now with radioactive chemicals coursing through his veins. I keep telling Holly to try not to worry too much. I tell her that this is always how superheroes are born.

As footnote: I can't sleep tonight. The strain and stress of the coming transplant have rendered my mind's shutters useless, and they've been stuck wide open for the last three days or so. Last night I cleaned our house (which is an empty, lonely place since Holly and Jeremy took up residence here at the hospital again) within an inch of its life. Tonight I wandered the vacant hallways of the hospital, eventually making my way down to the ground floor, where there is a bay of vending machines filled with all manner of bad food. I walked over to the only Coke machine I've found in the entire hospital that dispenses cans rather than those plastic bottles (Holly thinks I'm completely mental, but I swear the soda tastes different from one container versus the other, and I much prefer the cans), deposited 65 cents, and pressed the button for regular Coca-Cola. There was a huge CRASH! from inside the machine, and I watched in amazement as the issuing chute at the bottom of the machine filled with cans. For my 65 cents, I was dispensed nine ice cold Cokes.

It may seem silly, but I believe that providence can announce itself in silly ways sometimes. It was just after midnight when I pushed that button. I feel lucky today.

No comments:

Post a Comment